Albania's Economic Model

A comprehensive study of the economic fundamentals, dependency on illicit money, consequences and solutions

Albanian Conservative Institute

9/8/202531 min read

Background and definition of narcostate

In the landscape of emerging European economies, Albania presents a paradox of apparent resilience amid profound fragility. This analysis reveals an economy increasingly entangled in the web of illicit activities, particularly drug trafficking, unsustainable in the medium to long term.

We have to say at the beginning that our intention is not to present our country in a bad light. Rather, moved by disturbing elements in the Albanian economy, as experts, we aim to present a complete overview of the economy and a new vision with the respective policy recommendations that will save it and prepare the country in its European integration.

Albania, a NATO country, finds itself in a demographic catastrophe, with close to 1.1 million citizens having fled the country, legally and illegally to the Schengen area, according to EUROSTAT. UN and European demographic data indicate that Albania is experiencing one of the fastest declines in birth rates globally, and among the most severe in Europe. In the first half of 2025, the fall in new births was 6.5% compared to the same period of last year. In the first nine months of 2025, there were 4.6% fewer births than in the same period of the previous year. 2024 marked a decline of 5% compared to 2023. 2021 was the first year on record in which the number of yearly births (27,211) was lower than the number of deaths (30,507). In the first half of 2025, again the natural change was negative. From one of the youngest populations in Europe, Albania is becoming a dying nation, which deeply worries us as scholars.

Albania has in recent years increasingly been labeled a "narcostate" or as having a “narcoeconomy” by national and international media and foreign experts, a term that denotes a country where drug trafficking significantly affects the economy, politics, and institutions.

The Independent (2019) describes Albania as "the center of drug trafficking in Europe", highlighting its role in cannabis production and cocaine transit. Similarly, Proto Thema (2019) calls it "Europe's first narco-state", indicating the extent of organized crime.

BBC (2024) reinforces this by calling Albania the "marijuana capital of Europe", citing its dominance in the regional supply of cannabis. These characterizations stem from Albania’s strategic location on the Adriatic, weak post-communist institutions, and widespread corruption, as highlighted in The Guardian (2019), which detailed the global cocaine networks of the Albanian mafia. Recent arrests, as well as reports by media such as the Telegraph, show the considerable amounts of cocaine being transported in the main port of Albania, and the immense sums of money being involved, validating earlier media and institutional reports.

Unless otherwise stated, this study uses Albania’s nominal GDP as reported by INSTAT and the World Bank, converted to euros at the annual average exchange rate of the respective year. Nominal GDP is estimated at approximately €27 billion in 2024 and projected at €29–30 billion in 2025.

This labeling reflects a dual reality: a formal economy with a GDP of EUR 27 billion in 2024 and projected around EUR 29.9 billion in 2025, and a shadow economy estimated at 30–35% of GDP (~EUR 8 – 9.5 billion). This contrasts sharply with the EU average shadow or informal economy of 10%, underscoring Albania’s exceptional status in Europe. As policy experts, we set out to study what part of this shadow economy comes from illegal activity and what the repercussions are.

Economic Impact of the Drug Trade

The scale of the drug trade is considerable, forming a shadowy undercurrent that buoys the visible economy while eroding its foundations. Media and investigative reporting have cited gross turnover figures for cannabis and cocaine trafficking linked to Albanian criminal networks reaching several billion euros annually. These figures represent upper-bound estimates of total market value, not the share captured or absorbed within the Albanian economy. This study therefore focuses not on gross criminal turnover, but on observable macroeconomic transmission channels, foreign-exchange pressures, construction financing gaps, trade imbalances, and sectoral distortions, which indicate a substantial but unquantifiable domestic absorption of illicit proceeds.

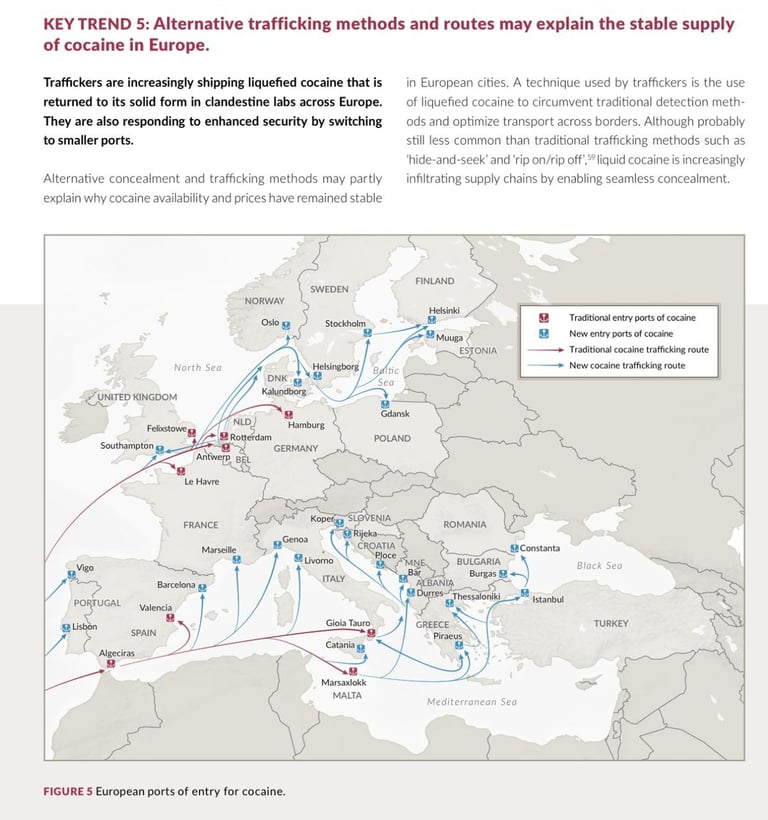

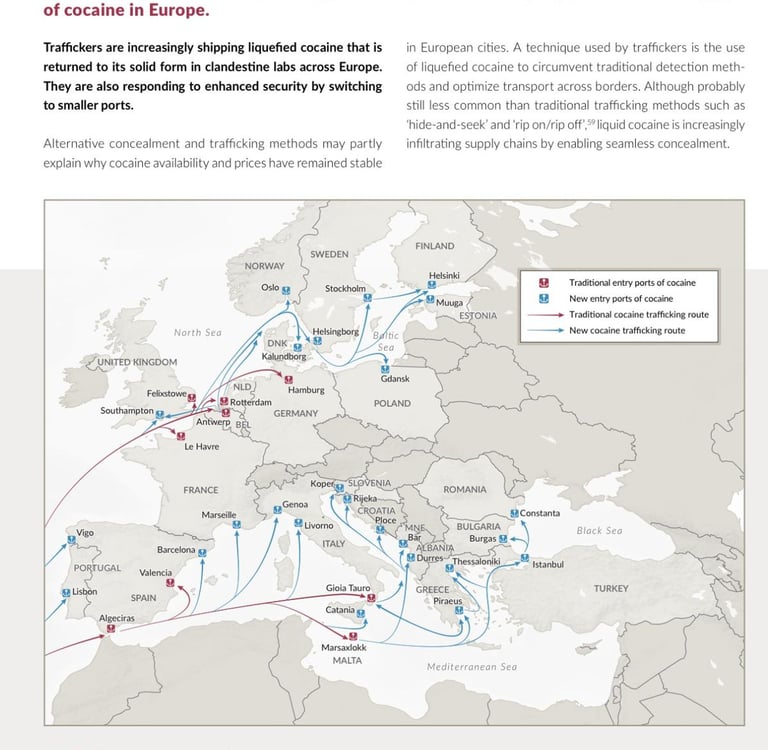

According to UNODC, Albania has become in recent years one of the main transit countries for heroin and cocaine trafficking, with links to Latin American countries, from where it goes to European Union countries, Latin America or the USA.

In 2022, the same report mentioned Albania as one of the main countries for cannabis cultivation, seventh in the world, and first in the South-Eastern European region. This report mentions Albania as a transit point for heroin that starts from Pakistan, passes through Syria, Turkey, Greece, Albania and then to Western European countries.

This flow deforms the economy and brings extremely serious consequences for the well-being of every citizen, not only for the deformation of the economy, but also for what will come next, the moment the tap of dirty money is turned off. The Guardian (2019) and Insider (2023) report that drug profits are laundered through construction, fueling a 6.8% growth in the sector.

CityAM (2023) notes that the “shining towers” in Tirana reflect this illicit capital, with around 20% of construction funds ($0.36 billion) being informal. Tourism also benefits indirectly, but manufacturing, perhaps the most important sector, which has fallen from 11% in 2015 to 9% of GDP in 2023, suffers from neglect. The CityAM Reporting states that “though living standards have improved considerably since that time, its failure to transform into a true market economy has handed power to drug lords and driven the brightest and best to emigrate. Of course, there are no official figures, but the country is now referred to as the “Colombia of Europe”. Estimates suggest that between a third and a half of Albania’s gross national product comes from drug trafficking. In any case, several billion euros are generated from drug trafficking every year.”[1]

Definition of a Narcostate

According to Collins dictionary, a narcostate is a country in which the illegal trade in narcotic drugs forms a substantial part of the economy.

Scholars find that there are differentiations between various narco states. However, all of them have in common some degree of the following:

· Drugs dominate key sectors.

· Institutional capture (judges, members of parliament, senior officials, government cabinet).

· Dependence on international anti-drug interventions.

These criteria are consistent with those used in academic and policy literature on narco‑states and criminalized states (e.g. Shelley, UNODC, GI‑TOC). Albania displays multiple indicators consistent with a narco-economy, though precise quantification remains difficult.

Across multiple sources, plausible estimates of domestically absorbed illicit proceeds range from 15% to 20% of GDP, with the EUR 4 billion estimate being the most recurring[2], while core productive sectors such as industry and agriculture wither under neglect. This has been the lowest estimate we could find, with the highest being the CityAM estimate of up to half of GDP. An early 2024 Sunday Times[3] reportage on Albania mentioned that in 2023, EUR 2.85 billion invested in construction were not through banks. Even if we were to remove remittances, the amount coming from drug money is considerable. Large seizures in European ports underscore the scale of networks, reinforcing the risk that illicit proceeds materially distort Albania’s domestic economy.

Nine years ago, when the main issue was mostly cannabis cultivation and Albania had not yet become a major hub for cocaine and heroin, the European Union[4] estimated that Albania’s drug industry accounted for 2.6 percent of the country’s GDP. According to the EU progress report, revenues generated by the narcotics trade represented a significant share of the Albanian economy and, when compared with developed countries, are up to 300 times higher; in Western economies such as France, Italy, Germany, or the United Kingdom, the drug industry’s weight in national output range from just 0.07 percent to 0.19 percent. At an estimated 2.6 percent of GDP in 2016-2017, the drug economy in Albania generated a turnover equivalent to the entire public and private education sector or to the whole hospitality and restaurant sector combined.

According to a 2025 report in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, only in one seized shipment sent to Hamburg by an Albanian gang, there was cocaine worth between EUR 1.5 billion and EUR 3.5 billion, the largest cocaine seizure. There are other criminal groups operating in Albania that send cocaine and heroin towards Europe worth billions of euros. [5]

As a recent Altax study showed, drawing on national and international data, such as World Bank reports, Global Financial Integrity assessments, and domestic GDP figures, in Albania alone, informal and illicit financial flows together may account for up to 4-5 billion USD, or nearly 20-25% of GDP, depending on year and methodology.[6] Even if we assume that €1 billion of informal inflows are non-criminal, family remittances, tax evasion, legacy cash, the remaining €4 billion still represents an extraordinary criminal dependency. Altax estimates 20–25% of GDP in some years; our conservative synthesis uses a lower bound of ~15%, which is still considerable and comparable to more established narco-states in Latin America.

Although remittances amount to roughly €1.4 billion annually, the majority enter Albania through formal channels; at most €400–600 million can be considered informal, leaving the bulk of informal inflows to be explained by other, often criminal, sources.

This money deeply impacts and distorts Albania’s economy and elections, as the OSCE report showed. [7]Albanian cartels have become major players in the cocaine world trade, and Albania a new route in the Balkans.[8][9][10]

The United States Department of State Report on Narcotics, states that “Albanian-led criminal groups in particular have played a significant and increasingly sophisticated role in supplying international markets with illicit drugs, expanding trafficking routes from Latin America to European Union countries, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and exploiting aspects of the Albanian economy to fuel corruption and financial crime.”[12]

“Albanian-led organized crime groups play a significant role in supplying international markets for cannabis, cocaine, and heroin, according to Albanian law enforcement authorities. These Albanian-led organized crime groups exhibit increasingly sophisticated crimes, communications, and money laundering techniques. They operate across the Balkans as well as in the European Union (EU), the United States, Canada, South America, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, and Turkey. Albanian criminal networks have direct access to cocaine production in South America and trafficking networks bringing cocaine into Europe and the United Kingdom. They use the Albanian economy, particularly the construction sector, to launder proceeds and contribute to corruption. Violent crime in Albania, including assassinations, is often associated with organized crime, and judges, prosecutors, police, politicians, journalists, and activists have been subjected to intimidation. Albania participates in the Global Coalition to Address Synthetic Drug Threats, but during this reporting period officials did not report seizing fentanyl or other synthetic drugs in significant amounts. Corruption, weak rule of law, and unemployment drive Albania's drug trafficking problem.”[13]

ARTE Europe Weekly

The ARTE Europe Weekly reportage is built around one provocative central question: Is the EU “flirting with a narco-state” by advancing Albania’s accession process?

To answer this, the reportage weaves together three parallel storylines:

· The rise of Albanian organized crime in Europe, especially in cocaine trafficking

· Alleged links between criminal networks and Albanian political power

· Why the EU continues to fast-track Albania anyway, despite corruption indicators

A. Albanian organized crime as a European threat

The reportage asserts that:

· Albanian criminal groups are now among the top five most dangerous networks in Europe, citing Europol.

· Cocaine seizures in the EU have increased fivefold in a decade, reaching 419 tons in 2023.

· Albanian networks dominate: Belgium & the Netherlands (especially the Port of Antwerp), Italy, Spain, Germany, France, The UK (described as Europe’s largest cocaine market),

Albanian groups are depicted as highly professional, transnational, operating directly from Latin American production sites. This part of the report is fact-heavy and largely relies on law-enforcement data.

B. From crime to politics: alleged state capture

Criminal money has according to ARTE penetrated the judiciary and government. Elections under PM Edi Rama are portrayed as questionable. Authorities are accused of turning a blind eye, or actively protecting the “shadow economy”

Cases mentioned:

· Meeting between Rama and a representative of the Sinaloa cartel accused of money laundering through a casino whose license was given by the Albanian government after the meeting with the PM.

· The former Interior Minister case (Tahiri).

The takeaway pushed here is selective justice: Whistleblowers and law-enforcement officers suffer, while government officials escape.

C. Poverty as a structural enabler

The reportage emphasizes:

· Albania as one of Europe’s poorest countries

· 1 in 5 people below the poverty line

· High youth unemployment

· Entire families become economically dependent on criminal networks. The drug economy is not marginal, but systemic[14]

D. Judicial reform & vetting

Although the EU highlights:

Vetting of judges

Anti-corruption agencies

Special prosecutors

The report claims:

Vetting may have been politicized

Vetting bodies have been used to eliminate:

Unfriendly judges

Internal rivals

Reform has become a tool of power consolidation, not rule of law

The 2025 Global Organized Crime Index report on Albania states that “the heroin trade in Albania is highly organized, with the country serving as both a transit and distribution hub. Albanian criminal groups play a crucial role in smuggling Afghan heroin into Europe through the Balkan route. Albania primarily functions as a transit country for heroin trafficked from Türkiye, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan along the Balkan route to Europe. Most heroin enters Albania by land through North Macedonia and Kosovo and several internal heroin-processing laboratories have also been uncovered by the Albanian police in the past. Although local consumption remains limited, heroin trafficking generates substantial profits for organized crime. Law enforcement efforts have resulted in periodic seizures; however, the market remains resilient due to transnational trafficking networks and corruption among border control personnel.

Albania has emerged as a key player in the European cocaine trade, with organized criminal groups facilitating the movement of substantial quantities from Latin America. The Port of Durrës serves as a major entry point for these shipments, which are often concealed within cargo containers. Albanian traffickers maintain strong ties with suppliers in Colombia and Ecuador, enabling them to expand their influence in European cocaine markets. In addition to maritime shipments, organized crime groups are increasingly utilizing overland routes through Spain and the Netherlands to distribute cocaine across the continent. Despite notable arrests and drug seizures, cocaine trafficking continues to be a prevalent criminal activity. Cannabis remains the most prevalent illicit drug traded in Albania, with domestic cultivation continuing despite law enforcement crackdowns. The shift from outdoor to indoor cultivation has made detection more challenging, as greenhouses and hydroponic systems are employed to support year-round production. Albanian criminal groups dominate cannabis supply chains in Western Europe, particularly in the UK and Spain. Although Albania legalized medical cannabis in 2023, the illicit market persists, driven by high demand and established trafficking networks that utilize encrypted communication platforms to coordinate shipments.

The synthetic drug trade, although smaller than other drug markets, has experienced growth in recent years. Substances such as MDMA, amphetamines and methamphetamine are becoming increasingly prevalent, particularly in urban nightlife and tourist hotspots. These synthetic drugs are often smuggled from neighbouring countries, with Albania primarily serving as a destination point. Albanian criminal groups have formed partnerships with producers based in the Netherlands and the Balkans to supply synthetic drugs to both local and international markets. Law enforcement efforts have concentrated on disrupting distribution networks; however, the rapid evolution of synthetic drug markets continues to increase availability and presents ongoing challenges for detection.

Albanian criminal networks are among the most influential in the region, operating both domestically and internationally. They engage in a variety of illicit activities, including drug trafficking, arms smuggling, contract killings and human trafficking. Recent findings indicate that Albanian criminal networks dominate the cocaine trade in Europe, maintaining strong connections with suppliers in Latin America. Additionally, these groups have established deep-rooted connections to Turkish and Kosovar criminal organizations, further strengthening their influence in both regional and transnational markets. Violence continues to be a prominent feature of Albanian criminal networks. Several cases of contract killings and targeted assassinations have been reported, particularly in urban areas.

Corruption within Albania’s political and law enforcement institutions continues to facilitate organized crime. Investigations utilizing encrypted communication platforms have revealed deep ties between high-ranking officials and criminal actors. Several police officers and judicial officials have been implicated in aiding criminal networks, with some directly engaging in illegal activities. The involvement of state-embedded actors extends to public tenders and government contracts, where criminal groups employ bribery and blackmail to secure lucrative deals

While Albanian criminal groups dominate the country’s organized crime landscape, foreign actors maintain a presence, particularly in human smuggling and drug trafficking. Reports indicate that Palestinian, Iraqi, Iranian and Moroccan criminal groups are active in human smuggling operations. Turkish criminal organizations control heroin trafficking routes into Albania, while Italian mafia groups maintain influence in southern Albania and Tirana. Additionally, the Russian criminal underworld has been linked to Albanian criminal organizations, although their cooperation appears to be limited compared to other foreign networks.

The private sector in Albania, particularly the construction, real estate and gambling industries, plays a role in money laundering and illicit financial flows. Criminal organizations exploit these sectors to launder proceeds from drug trafficking and other illegal activities. While the government has imposed partial bans on gambling, criminal infiltration remains pervasive, especially in urban and tourist areas. Reports indicate that several businesses in these areas have direct ties to criminal groups, with hotels and resorts often serving as fronts for money laundering operations.”[15]

Construction is a high return sector (15%-25% ROI), that is why illegal money is channeled there, compared to agriculture or industry, even if the first is a low value-added sector, compared to high value-added ones like production. In 2024, an interesting fact is that bank credit for construction was only 22%, raising the question of how the majority of the constructions were financed. According to central bank data, new construction loans amounted to 380 million euros and new housing loans to 467 million euros. According to Bank of Albania data, new construction and housing loans totaled approximately €847 million in 2024. When compared with total estimated construction investment based on permits, sectoral output, and market valuations, bank financing accounts for roughly 22% of activity.

This model is inherently unsustainable. Under a scenario where illicit inflows are significantly curtailed, Albania would likely face a sharp short‑term contraction. In recent years, US administrations have intensified efforts against transnational drug cartels and the governments that enable them. Additionally, the European Union has often strongly urged governments in and out of the EU to fight criminal activities and their impact on the economy. If the Albanian economy is indeed massively sustained by such informal or illegal money flowing in and nothing else, then we are facing a huge risk to our economy. Considering the other corruption scandals involving the deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Energy and Infrastructure[16] [17][18], the AKSHI scandal[19][20][21][22][23] and other corruption affairs[24] discovered in recent years, the collapse of cybersecurity and the infiltration of Russian and other adverse companies and influences, including those under investigation by NATO, and the massive impact of drug money, the problem is not solely Albanian, but a NATO and EU one as well.

This dependency not only undermines the principles of economic liberty and national sovereignty but also erodes the very fabric of a free-market system. Albania's path forward demands decisive reforms: slashing taxes to unleash productive forces, dismantling centralized state controls that stifle competition, and severing ties with criminal networks through rigorous enforcement. Without such measures, the illusion of progress will shatter, leaving a nation vulnerable to collapse. Credible reports moreover show the impact of this economic model on Albanian democracy, the erosion of standards, the lack of free and fair elections, and accumulation of power. The European Parliament must condition further integration on these imperatives to foster genuine, inclusive development.

The Albanian Economy: Characteristics, Traits, and What Sustains It

Albania's economic landscape, shaped by its post-communist heritage, reveals a nation at a crossroads, poised for integration into the European fold yet hampered by deep-seated distortions that prioritize short-term gains for a few over enduring prosperity for all. With a GDP of €27 billion in 2024, Albania operates as a small, open economy heavily reliant on remittances, construction, and services. Remittances alone contribute around €1.4 billion annually, or 8% of GDP (Bank of Albania Balance of Payments, 2024), while tourism and related services have surged to represent 25% of economic output (INSTAT Tourism Statistics, 2024), although INSTAT reports that even this sector that had held the economy in recent years, has shown a slowdown in 2025.

At its core, Albania's economy exhibits traits of vulnerability: High emigration rates drain human capital, with a total of 1.1 million (roughly 40% of the population), according to EUROSTAT and other sources, having left since 2014 toward the Schengen area alone, not considering emigration toward the US and the UK, while productivity has declined, averaging a -1.2% annual drop from 2023 to 2025 (INSTAT National Accounts 2025). In the first quarter of 2025, out of EUR 362 million in FDI, EUR 110 million were in the real estate sector, and EUR 71 million were in financial activity, while industry and energy marked declines. The share of real estate investments in total foreign direct investments has increased from 5.7% in 2014 to 29% in the first quarter of this year, showing that even the yearly rise in FDI does not come from big investors in competitive or productive industries.

Indeed, to make up for the considerable depopulation and shortfall in workforce, the official policy of the government, as stated by the Prime Minister himself in 2021, is to bring people to the country from Asia and Africa, who in most cases try to illegally enter the EU, creating a new migrant route. Albanians leave because of higher costs of living, few opportunities in the market, lack of quality education and healthcare and problems with rule of law and life safety in the streets. This brain drain, in turn, is one of the most important factors affecting the economy and the labor market. Meanwhile, as there are labor shortages, the foreign currency illicit flows are channeled into construction and services, driving up prices, while the purchasing power of those remaining in the country goes down.

A critical but often overlooked characteristic is the extensive government involvement in the market, which centralizes economic activity and stifles the emergence of a true free market. In Albania, the state maintains a heavy hand through pervasive regulations, subsidies, and direct interventions that favor politically connected entities over competitive enterprises. For instance, public procurement processes are frequently awarded to firms with ties to ruling elites, as highlighted in State Department Investment Climate Statements (2024), which note widespread corruption and favoritism in tenders.

This report also mentions “foreign investors perceive Albania as a difficult place to do business. They cite corruption, including in the public sector, the judiciary, public procurements, unfair and distorted competition, large informal economy, money laundering, frequent changes to fiscal legislation, and weak enforcement of contracts as continuing challenges for investment and business in Albania. The emigration of young, skilled labor has created labor shortages that affect investment prospects. Albania continues to score poorly on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. In 2023, Albania ranked 98 out of 180 countries, a slight improvement from 2022 but still lagging behind its best ranking of 2016, when it ranked 83rd out of 176 economies.

Albania suffers from a large informal sector and money laundering activities. The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) included Albania in its grey list in 2020. From 2020-2022, the country underwent four follow-up reports and improved its performance in technical compliance, resulting in removal from the grey list in October 2023. The business community reports that the large influx of illicit proceeds from drug trafficking, smuggling, fiscal evasion, and corruption distorts competition in the market. Allegations of corruption are common, and investors report that they can be the target of extortion by public administration, media, and criminal groups.

Reports of corruption in government procurement are common, with investors frequently reporting cases of government corruption delaying and preventing investments in Albania. The continued use of public private partnership (PPP) contracts has reduced opportunities for competition, including by foreign investors, in infrastructure and other sectors. Weak analysis and a lack of technical expertise in drafting and monitoring PPP contracts are ongoing concerns. Several U.S. investors have faced contentious commercial disputes with both public and private entities, including some that went to international arbitration.

Property rights continue to be a challenge in Albania because clear title is difficult to obtain. There have been instances of individuals allegedly manipulating the court system to obtain illegal land titles. Overlapping property titles are widespread issues. The compensation process for land confiscated by the former communist regime continues to be cumbersome, inefficient, and inadequate. The government has stated a will to address this problem, but progress has been halting.”

In the 2024 Investment Climate Statement for Albania, the report describes "state capture" as a term for systemic corruption where ruling parties exert undue influence over state institutions, contributing to an uneven playing field for investors. Earlier reports, such as the 2021 Investment Climate Statement, similarly reference state capture in Albania, linking it to corruption and political interference in the judiciary and economy.

The State Department's 2024 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Albania, published in August 2025, reports on censorship and self-censorship of the media, and the pressure exerted by the government and criminal groups on the media and journalists.

The European Commission and European Parliament have explicitly identified state capture in Albania in enlargement and progress reports, often as part of critiques on democratic backsliding and corruption in the Western Balkans. Key examples include:

Ø The 2018 Communication on a Credible Enlargement Perspective for the Western Balkans states that countries in the region, including Albania, "show clear elements of state capture, including links with organized crime and corruption at all levels of government and administration."

Ø The 2020 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy notes limited progress on addressing state capture in Albania, emphasizing the need to root it out for EU accession.

Ø More recent reports, such as the 2024 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, reiterate risks related to state capture as a major challenge, with specific references to Albania's ongoing judicial and anti-corruption reforms.

This centralization extends to sectors like energy and infrastructure, where state-owned enterprises dominate, and private competition is hampered by bureaucratic hurdles and arbitrary licensing. The result is a quasi-command economy disguised as market-oriented, where innovation is suppressed, and resources are allocated based on cronyism rather than efficiency. This not only perpetuates the shadow economy but also discourages foreign direct investment in productive areas, as legitimate businesses face unfair competition from state-favored or illicit-backed players. In essence, Albania lacks a genuine free market, replaced by a centralized system that amplifies distortions from illicit flows and hinders supply-side dynamism.

Unsustainability looms large: Construction bubbles, with vacancy rates of 32.9-40% (UNECE 2024; Pamfleti 2024), and declining productivity signal an impending correction, and potentially a full-blown crisis, in the moment that the illicit money flows are disrupted, leaving the Albanian citizen unprotected. In 2012 and 2013, it was estimated that for construction to keep a decent share in the economy, 1 million square meters needed to be built annually across the country.

Currently, only in the capital, there are permits issued for 2 to 3 million square meters. In the last seven years, solely in Tirana construction permits for 12 million square meters have been granted, most of which in and around the city center. Meanwhile, in 2023, there were 51,129 empty apartments out of the total of 292,000. The number of empty apartments has tripled from 2018 to 2023.

In 2022, a CO-Plan Institute study showed that Tirana had the highest population density in Europe, and the highest construction density in Europe. The capital has 20,000 residents per square kilometer, four times more than the EU average. CO-PLAN and related studies highlight severe air-pollution levels in Tirana, with long-term exposure associated with significant estimated premature mortality.

Without reforms to dismantle this centralized grip and illicit dependencies, Albania risks a profound economic unraveling, where the facade of progress crumbles under the weight of its own distortions.

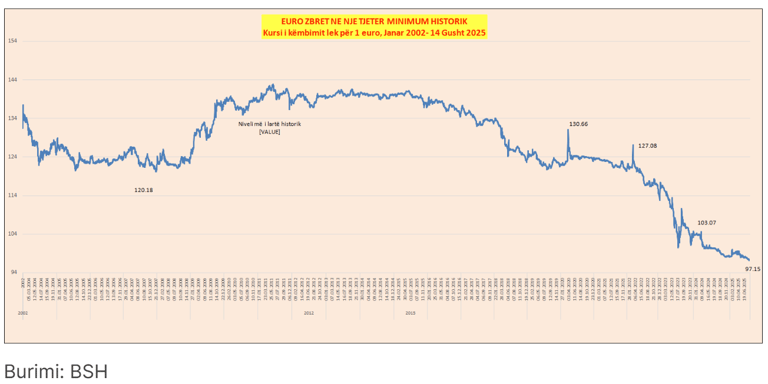

Euro Depreciation

The euro's depreciation against the lek cannot be adequately explained by conventional economic fundamentals. In a healthy economy, currency appreciation typically signals a strengthening economy. However, Albania's case defies this logic, as GDP growth has slowed in recent quarters and years, even with the boost in government spending, and is forecast to slow further. The goods trade deficit widened -25.3% of GDP in the first half of 2025 (INSTAT), and remittances grew modestly by 8% to €1.4 billion (stable as a share of GDP), and foreign direct investment remained at €1.6 billion (Bank of Albania 2024). The LEK appreciation started in 2015, the year when in Albania the massive cannabization of the country occurred.

This appreciation cannot be fully explained by recorded fundamentals alone and is consistent with substantial unaccounted foreign-exchange inflows, including illicit proceeds. These funds, often in euros from European markets, flood the domestic Forex market, increasing supply and driving up the lek's value without corresponding improvements in productive capacity. Rather than stemming from efficiency gains or innovation, this "strength" masks underlying weaknesses, such as declining industrial output (-7.73% in 2024, INSTAT) and declining exports (€4 billion total, UN Comtrade 2024).

The Bank of Albania's response has been measured but limited in efficacy. To mitigate the appreciation's harm to exporters, particularly in manufacturing, where competitiveness erodes, the central bank intervened through foreign exchange purchases totaling €933 million in 2024 and EUR 800 million (BoA), aiming to absorb excess euros and stabilize the rate. The volume of the foreign exchange market in Albania reached USD 11billion in 2024. Nevertheless, the euro continued to depreciate, which shows the huge amount of euros in circulation.

Growth Trends (2022-2025) and Contributors

Albania's growth has decelerated but remains positive, driven by non-productive sectors. From a macroeconomic standpoint, this reflects a classic imbalance: Demand from illicit capital inflates non-tradable sectors (construction/services), while tradables (industry/agriculture) suffer from underinvestment, leading to persistent trade deficits and vulnerability to external shocks. The result is growth that appears robust on aggregate but fails to build sustainable productive capacity, as evidenced by declining shares in industry and agriculture.

v 2022: 4.83% (INSTAT). Construction +12% (1.5 p.p. contribution, INSTAT National Accounts, 2023), services +8% (2.0 p.p.). Industry +2% (0.2 p.p.), agriculture stagnant (0% contribution).

v 2023: 3.94% (INSTAT). Construction +10.3% (1.4 p.p.), services +6.5% (1.8 p.p.). Industry -3.2% (-0.3 p.p., INSTAT), agriculture -1.2% (-0.2 p.p.).

v 2024: 3.96% (INSTAT). Construction +4.52% (0.5 p.p.), services +6.51% (3.2 p.p. from subsectors like public admin +11.35%). Industry -7.73% (-0.8 p.p.), agriculture -2.70% (-0.4 p.p.).

v 2025 Forecast: 3.4%-3.7%. Q1 construction +1.78% (0.16 p.p.), services +2.12% (trade/transport, 0.33 p.p.). Industry -5.66% (-0.66 p.p.), agriculture -2.76% (-0.46 p.p.).

v 2026 Forecast: 3.5% (World Bank), while the IMF foresees a 3.6% growth.

The trend in growth is declining, and this considering the illicit flows sustaining the economy remain as they are. However, if due to the war on cartels by the US or other entities, these flows are disrupted, the Albanian economy is projected to fall into recession territory.

Sectoral GDP Shares (2024, INSTAT):

Ø Construction: 11.92% (up from 11.52% in 2023).

Ø Services: 48.69% (trade/transport/accommodation +2.12% growth).

Ø Industry/Production: 10.48% (down from 11.52%).

Ø Agriculture: 15.45% (down from 16.27%. It used to be 20% of GDP only a few years ago).

Decline in Production and Unsustainable Economic Model

Albania enters fiscal and calendar year 2026 carrying all the symptoms of a failed economic model: production has been shrinking for years, exports are falling, agriculture and industry are in prolonged recession, and the working-age population is leaving at alarming rates.

The country “grows” on paper but becomes noticeably poorer in everyday reality. Instead of expanding supply, productive capital, and higher value-added investment, the state continues to lean on construction (where numerous foreign and domestic sources state that dirty money is channelled and laundered), tourism, and government spending. But even tourism grew at a slower pace this year compared to last year, while in construction there are signs of deceleration as well, such as a decline in concrete production.

Independent analyses confirm this picture: the rise in government revenues comes mainly from consumption (VAT as the core component, increasing because of higher prices rather than higher quantities consumed), not from production; meanwhile core inflation (food/energy) is swallowing the nominal gains from wages and pensions. In practice, we have a fictitious stability on paper, not real development.

At first glance, macroeconomic indicators look “stable”: headline inflation has fallen to 2.8%, the budget deficit is kept below 2.3% of GDP, and public debt stands at 53.6%.

In substance, Albanian growth is increasingly driven by non-tradable sectors and public expenditure rather than productivity-enhancing investment in tradables. According to INSTAT data, over 60% of GDP growth in 2025 came from household consumption (which is largely spending on food and basic items) and public administration, while the contribution of the productive sector has been negative: agriculture −2.5% and industry −1.8% in the second quarter of 2025 (INSTAT).

The year 2020 began with strong growth of 5.2% in the first quarter, followed by +3.6% in the second quarter, but the decline in agriculture started in the second half of 2020 and never stopped. From 2021, the crisis deepened. The first and second quarters recorded declines of −1.6% and −3.8%, followed by −1.1%, bringing annual production that year down by −1.6%. In 2022 the decline deepened further to −4.8%. The same contraction continued in 2023 and 2024, at −1.3% and −2% respectively.

Industry is the other sector that has fallen into recession. The decline in this sector began in the first quarter of 2024 and seems to have deepened in the first quarter of this year by 5.7%. The industry sector includes heavy industry activities such as mining or quarrying, electricity, oil, water or waste management as well as the processing industry, which includes activities such as clothing or footwear. Light industry began its decline in the second quarter of 2023 and in the first quarter of this year, the decline seems to have deepened to minus 7.5% in annual terms.

Utilization of productive capacity fell significantly during 2025, while the economic sentiment indicator dropped by 1.3 points in September, signaling weak expectations for 2026. These are not just numbers: they indicate that businesses are producing less and citizens are consuming less, despite increases in the minimum wage or the average wage.

The reported growth of 3.9% in 2025, which the Ministry of Finance expects to reach 4% in 2026 (still insufficient for a country like Albania), is in fact growth driven by public spending and construction. According to the IMF’s latest forecast, the growth projection for 2025 was lowered to 3.4%, from 3.8% in the IMF’s own spring report. The World Bank forecasts 3.1% growth for 2026, while the European Commission’s forecast is 3.5%, both far from the government’s projected 4%.

According to INSTAT, public administration, education, and health contributed +1.65 percentage points to GDP in Q2 2025 (with 17% growth compared to the same period a year earlier), while agriculture and industry contributed negatively (−0.46 and −0.18 pp). This means the economy is being propped up by the state itself, through wages, bonuses, and other public expenditures, rather than by private initiative or production.

If a country grows only through state spending, but not through production and exports, it is not becoming richer, it is becoming more dependent. Albania is experiencing precisely this: an economy dependent on itself, where the state borrows to pay the state, or to finance public works, while dependence on dirty money continues to rise. If the productive private sector does not expand, any wage increases or headline economic growth are illusory and unsustainable in the medium term.

It should be understood that the public sector is financed by taxes paid by individuals and businesses, i.e., the private sector. The more the public sector expands, the more the private sector shrinks, until the money that keeps the state standing runs out.

Household Costs

According to INSTAT data for 2025, household income has not yet crossed the threshold at which consumption becomes diversified: families spend around 39.6% of their budget on food (the highest in Europe). Inflation over the first nine months of 2025 is around 2.4%, while food prices rose 1.8% year-on-year, with the most visible swings in oils and fats, milk, cheese, eggs, and meat. Energy and basic services increased by 4.1%. In poorer regions especially, household finances are centred on survival, not development or savings.

According to Monitor’s reporting, based on INSTAT household budget data, Albanian families in 2024 spent on average 93,000 lek per month on consumption, an increase of only 1.5% compared with 2023.

Labour Market and Emigration

In the first quarter of 2025, employment fell by 0.8%, while agriculture lost 9.3% of its jobs. Services are the only sector expanding, but not in stable employment, mainly through seasonal tourism and the public administration. At the same time, the number of pensioners who have returned to work has reached 120,000 people over age 65 (46% increase from 2023), a phenomenon that reflects both a shortage of human resources and the inability to survive on pensions.

On the other hand, emigration remains a fatal problem. This shrinkage of the labour force further reduces production, weakens the pension system, and makes the economy more fragile in the face of crises. The government has indirectly acknowledged this by proposing the import of Asian and African workers, a temporary solution, but in essence anti-national, replacing Albanians who have left rather than retaining those who want to stay.

The 3.4% economic growth in the first quarter of 2025 was helped by growth in the Public Administration sector by 19% and in the real estate sector by 8%. The “Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles, transportation and storage, hotels and food services” group, the group that in recent years has been at the forefront of economic growth, especially due to tourism, had a growth of 2.1% in the first quarter of this year, which suggests that the golden days may be over. This is the sector that in 2024 grew by over 5% and in 2023 by over 9%.

Likewise, the construction sector, which since the reconstruction process from the 2019 earthquake has been a sector with strong growth, in the first quarter of 2025 grew by 1.8%.

Monitor magazine highlights that Albania has the lowest FDI growth rates in the region for 2024, lagging behind the Balkan and Eastern and Central European countries, which are becoming centers of innovation and technology. However, Albania does not invest in these sectors of the future as in the countries of the region or elsewhere in Europe, focusing on construction.

Unfavorable structure of FDI: Despite the high level of FDI, their structure is one-sided and not encouraging. The real estate sector dominated with 270 million euros in the first 9 months of 2024, accounting for 23% of total FDI. Other sectors include financial activities (mainly growth in bank capital) with 17% and extractive industry with 14%. This shows clearly the need for diversification: The heavy dependence on tourism and construction hinders the diversification of the economy. The advantage of cheap labor has been lost, and Albania needs to modernize the production chain to move from low-cost production to value-added production.

The EBRD representative in Albania also makes the same call for a change in the economic model and diversification, emphasizing that the importance of value-added sectors is decreasing, leaving the Albanian economy dependent on two sectors, whose growth does not depend on a sustainable economic model.

Recommendations

Anti-drug short-term solutions

As seen, construction, as the highest-risk channel, absorbs the bulk of illicit funds, distorting markets and inflating bubbles that could burst with devastating effects. Below are a few targeted recommendations, aimed at reducing distortions to free up productive capital, while drawing on successful models from peers in the region like Serbia or the EU.

Ø Start an uncompromising fight against organized crime and drug cartels. A technical or caretaker government would be best suitable to doing this, aligning with international resolutions of EPP, IDU, CDI and taking into account the OSCE/ODIHR preliminary report, as well as the EU Commission’s report on Albania.

Ø Customs Strengthening: Allocate funds for advanced scanners at ports.

Ø Anti-Laundering Task Force: It will target construction laundering, free capital for productive use and raise productivity.

Ø Production Incentives: Subsidies for manufacturing/textiles, counter crowding-out, boost industry output, export, and lower costs and shift supply curve right.

Ø Informality Reduction: Enact supply side reforms to reduce informality, boost production and cut the size and reach of government.

Ø Modernization and strengthening of the intelligence service and counter-insurgency tools, including the import of dogs and other assets.

Ø Transparency: Mandate 100% tender audits. Corruption erodes FDI, turning away serious investors. With transparency, we can aim to attract legitimate capital.

Ø Exclusion of shell companies or companies registered in tax havens from participating in tenders.

We are confident that the situation in the country can change, and these proposals can be successfully implemented, if there is enough strong will from the government and the authorities, as should be expected from an EU candidate and a NATO member country.

Proposed solutions to change the economic model

Albania's current economic model, with its heavy reliance on nonproductive sectors like construction, tourism, and shadowy inflows, is a precarious edifice built on sand. To pivot toward a producing, exporting economy focused on innovation, technology, and AI, Albania must embrace a radical yet proven strategy: slashing taxes to unleash entrepreneurial energy, dismantling regulatory barriers that stifle competition, and curtailing government intervention and favoritism as well as wasteful spending to redirect resources toward productive investments.

Our vision is clear: Albania, with its young population, strategic location, and untapped potential in agriculture, agro-processing, tourism, energy independence, health services, and digital services, can become a regional exporter of high-value goods and innovations. But this requires massive, targeted investments in production, while fostering a low-tax environment (corporate and individual rates to 10% or below) that attracts global tech firms and startups, as well as a considerable improvement in the rule of law, democratic and living standards. Reduced regulations would cut business startup time and trim government expenses by 20-30%, freeing capital for infrastructure like tech parks and AI labs. The result? A shift from illicit-dependent bubbles to sustainable, export-led growth.

1. Lower Taxes to Ignite Supply-Side Dynamism

Taxes in Albania remain a drag on innovation compared to tech leaders like Estonia. To catalyze production and exports, slash the corporate tax to 10% and introduce a 0% rate on reinvested earnings in tech, AI, and manufacturing. For individuals, reduce the top personal rate to 10% and exempt startup founders from payroll taxes for the first three years.

Low taxes reduce the "deadweight loss" of government intervention, encouraging entrepreneurs to invest rather than evade.

2. Deregulate to Unleash Innovation and Production

Albania's regulatory burden, ranked 82nd globally for ease of doing business (World Bank 2024), chokes startups and manufacturers with licenses and bureaucratic delays. To focus on production, tech and AI, adopt a "one-in, three-out" rule: For every new regulation, eliminate three old ones. Streamline licensing to a single digital portal, cutting approval time to 48 hours, and create "innovation zones" in Durres and Vlora with zero local regulations for AI firms.

3. Slash Government Expenses to Redirect Resources

Government spending, at 30% of GDP (€7.5 billion in 2024, INSTAT), crowds out private investment through high deficits and inefficient bureaucracy. Cut non-essential expenses by 20-30%. Trim public administration, end wasteful subsidies and privatize state.

Furthermore, and more importantly, the state needs to stay out of the private sector and stop immediately favoritism toward its cronies, while ensuring freer and fairer competition. This intervention has caused international and prestigious firms to leave and has severely distorted Albania’s markets. There needs to be a clear separation of powers and move towards decentralization.

4. Focus on Exports, Tech, Energy, and AI: Building a New Engine

To export more, incentivize high-value goods: Tax credits for AI exporters (e.g., software firms) and free-trade zones with EU partners. Invest in AI education, grow the digital economy grew 15% annually.

Albania’s energy sector, 98% hydropower-dependent, is vulnerable to weather shocks but has vast renewable potential (527% capacity increase possible, energypedia.info). Reforms include: Production: Invest in solar and wind, and natural gas by 2028, leveraging auctions (e.g., Ministry of Energy’s solar plant, IEA). Offer tax exemptions for such projects. This could increase capacity, supporting also the creation of data centers (requiring 50-100 MW each).

Distribution: Upgrade grid infrastructure to reduce distribution losses. Improve efficiency of OSHEE. Integrate with regional grids for energy exports.

Storage: Invest in battery storage and pumped hydro to manage surplus production. Pilot AI-driven smart grids to optimize distribution, attracting data centers with reliable, cheap energy.

5. Strengthen Financial Markets

Albania’s financial sector is underdeveloped, limiting capital for entrepreneurship, energy and tech. Reforms include:

Capital Market Development

Fintech Growth

Access to Finance: Expand credit guarantees for SMEs in energy and tech. Lower interest rates via competition and central bank reforms. Introduce alternative ways of raising funds, such as crowdfunding.

Naturally, all our proposed reforms take into account the need for a reformed education system, to prepare Albanians about the challenges and reforms needed. There is a need to make human capital more competitive at an international level, by improving the education system and by providing incentives to businesses in training opportunities for their talents, as well as introduce policies that stop brain drain and enable brain gain.

Furthermore, we advise increasing capacities for Albanian businesses and NGOs to access EU-funding, in order for them to be able to compete with countries in the region.

This shift breaks dependency from illegal money, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation and prosperity. Albania can thrive, not as a transit hub for vice, but as a beacon of European ingenuity, innovation and production, becoming an added value for the EU as well. The time for action is now.

METHODOLOGY & DEFINITIONS ANNEX

Methodology and Definitions

GDP and Macroeconomic Data

This study relies on official data from INSTAT, the Bank of Albania, and the World Bank. Nominal GDP figures are reported in euros using annual average exchange rates. Growth rates refer to real volume changes unless otherwise stated.

Shadow Economy vs. Illicit Economy

The shadow economy includes all economic activity not fully captured in official statistics, encompassing both:

Informal but legal activity (undeclared wages, small cash services, underreported sales), and

Illicit activity (drug trafficking proceeds, corruption, organized crime revenues).

The illicit economy is therefore a subset of the shadow economy and should not be conflated with it.

Illicit Financial Flows

Estimates of illicit and informal financial flows (e.g., €4–5 billion annually) represent ranges, not point estimates. These figures combine multiple categories and should not be interpreted as the annual domestic value added of criminal activity.

Drug-Related Revenues

Figures cited in media and investigative reporting regarding drug markets typically refer to gross turnover or market value, often measured at destination or wholesale prices. These do not represent the share absorbed into Albania’s domestic economy. This study does not attempt to estimate domestic criminal value added directly; instead, it examines macroeconomic distortions consistent with large unrecorded inflows, including:

Exchange-rate appreciation,

Construction and real-estate financing gaps,

Trade-balance deterioration,

Sectoral crowding-out effects.

Causality

Where direct measurement is impossible, the study uses consistency-based inference: identifying outcomes that cannot be explained by recorded fundamentals alone and assessing whether illicit inflows provide a plausible explanatory mechanism. Causal claims are therefore expressed in probabilistic, not deterministic, terms.

Sources

[1] https://www.cityam.com/how-albania-went-from-europes-socialist-poorhouse-to-a-narco-state/

[2] https://kohajone.com/kryesore/ndertimi-eshte-sektori-me-i-madh-qe-lan-90-te-parave-e-pista-te-droges/

[3] https://www.thetimes.com/world/article/how-british-cocaine-users-are-funding-albanias-mini-dubai-9sqknlcks

[4] https://insajderi.com/industria-e-droges-peshe-domethenese-ne-ekonomine-e-shqiperise/

[5] https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/how-have-albanian-networks-come-to-dominate-cocaine-trafficking-to-europe/

[6] https://altax.al/en/product/money-laundering-in-albanian-economy-and-the-region-2025/#:~:text=This%20paper%20is%20conceived%20as,%2C%20governance%2C%20and%20public%20trust.

[7] https://odihr.osce.org/sites/default/files/f/documents/0/c/600028.pdf

[8] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn0w4e4e00jo

[9] https://www.ftm.eu/articles/albanian-mafia-threatens-europe

[10] https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/albanias-key-position-global-drug-trafficking-31834

[11] https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Observatory-of-Organized-Crime-in-Europe-European-Drug-Trends-Monitor-Issue-1-GI-TOC-December-2024.v4.pdf

[12] https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2025-International-Narcotics-Control-Strategy-Volume-1-Accessible.pdf

[13] https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2025-International-Narcotics-Control-Strategy-Volume-1-Accessible.pdf

[14] https://www.arte.tv/en/videos/112907-145-A/arte-europe-weekly/

[15] https://ocindex.net/assets/downloads/2025/english/ocindex_profile_albania_2025.pdf

[16] https://albaniavisit.com/tourism-politics/balluku-corruption-albania-deputy-pm/

[17] https://www.balkanweb.com/en/Balluk%27s-immunity-Lubonja%27s-corruption-of-the-deputy-prime-minister-an-unprecedented-crime-is-being-covered-up-by-Rama-the-protests-should-have-been-from-the-people-after-serious-scandals/#gsc.tab=0

[18] https://www.voxnews.al/english/politike/nen-hetim-per-11-tendera-me-vlere-11-miliard-euro-bardhi-balluku-po-ble-i109263

[19] https://www.hashtag.al/en/index.php/2026/01/19/dosja-akshi-kercenon-jo-vetem-shqiperine-po-shba-ne-e-nato-n-berisha/

[20] https://www.balkanweb.com/en/Akshi-Tabaku-scandal%3A-half-a-billion-euros-went-to-a-criminal-scheme--not-to-engineers/#gsc.tab=0

[21] https://balkaninsight.com/2025/12/16/eight-accused-in-albania-of-rigging-information-agency-tenders/

[22] https://www.alfapress.al/english/politike/kikia-afera-e-akshi-t-skandali-me-i-madh-ne-35-vjet-qe-konfirmoi-lidhje-i184309

[23] https://www.kapitali.al/english/lajme-nga-vendi/thellohet-skandali-vellai-gezim-hoxha-i-ambasadorit-shqiptar-ne--i36139

[24] https://www.voxnews.al/english/fokus/skema-e-skandalit-te-durana-tech-park-si-ishin-pergatitur-biznesment-e-dos-i108064